LaserChron Metadata Importer

Overview:

Along with analytical data importers, there may be a need for a metadata importer especially if analytical data comes from a separate source as the metadata. Consider analytical output from an instrument versus metadata in a field notebook. Metadata are important to give scientific context to analytical data. Well reported and well connected metadata makes it easier for a lab to use there own data as well as by others. Thus, metadata also makes a lab more findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (see importers).

Here we glance at an ongoing process to shape the metadata archive for Arizona LaserChron (ALC). At the end of this tutorial, you should have a foundation understanding for how to create your own metadata importer, including the two motifs of data cleaning and schema based importing as an iterative process (see importers).

Where to start?

Where to begin? ALC, like many labs, may have gigbites of archival data in different forms. In this case, a massive google drive housed information on countless of projects, many with important metadata about processed samples! The conundrum, how do we get the data out? The Sparrow suggested way would be to create a script, in any programming language, that parses data out of files that are similarly structured. Perhaps your lab uses a standard structure for record keeping in excel files.

Creating a one and done parsing script may not be feasible based on how much human variability the data records consist of. In this case, we recommend getting a hourly undergraduate worker to manually enter metadata. Kate Akin, a bright and enthusiastic undergrad at the University of Wisconsin Madison, helped us over the past few months collect sample metadata in a uniform, easily parsable, google sheet. You may wonder how efficient a process this really is or if it is worth it? In 4 months of part time work by Kate, she collected metadata for over 1500 samples by gathering it through both the ALC data archive and searching the primary literature. You can view the samples live on the ALC Sparrow instance.

Writing the Importer

At this point you have data that you want in Sparrow. It is some form where you can begin the iterative process of cleaning and parsing the data. Most likely you have an excel of csv file. This importer was written in Python, and if you have no other perference I highly recommend Python for it's relative ease to learn, write and the plethora of quality resources available. The easiest way to clean data in masse is to use the python library Pandas.

When writing importers, it's important to have an end data structure in mind. Specific data models require a specific data structure in order to be imported into Sparrow. The data structure needs to fit into the Sparrow Schema. For this importer we are focusing on the schema for the Sample data model. Based on the metadata we have, each sample will have some variation of the following data schema.

{

"name": "AME18-201",

"location": { "coordinates": [180, 90], "type": "Point" },

"material": "zircon",

"sample_geo_entity": [{ "geo_entity": { "name": "apex basalt" } }]

}

The data schemas can become complicated quickly, especially once you begin nesting. In this structure we are

nesting the sample_geo_entity model within the sample model and then the geo_entity within the sample_geo_entity model.

Getting the correct data schema is iterative process. Start simple and then build on complexity.

In the next couple sections we will go through the iterative process of cleaning and structuring the data for importing. The full code for this importer can be found here.

Cleaning the Data:

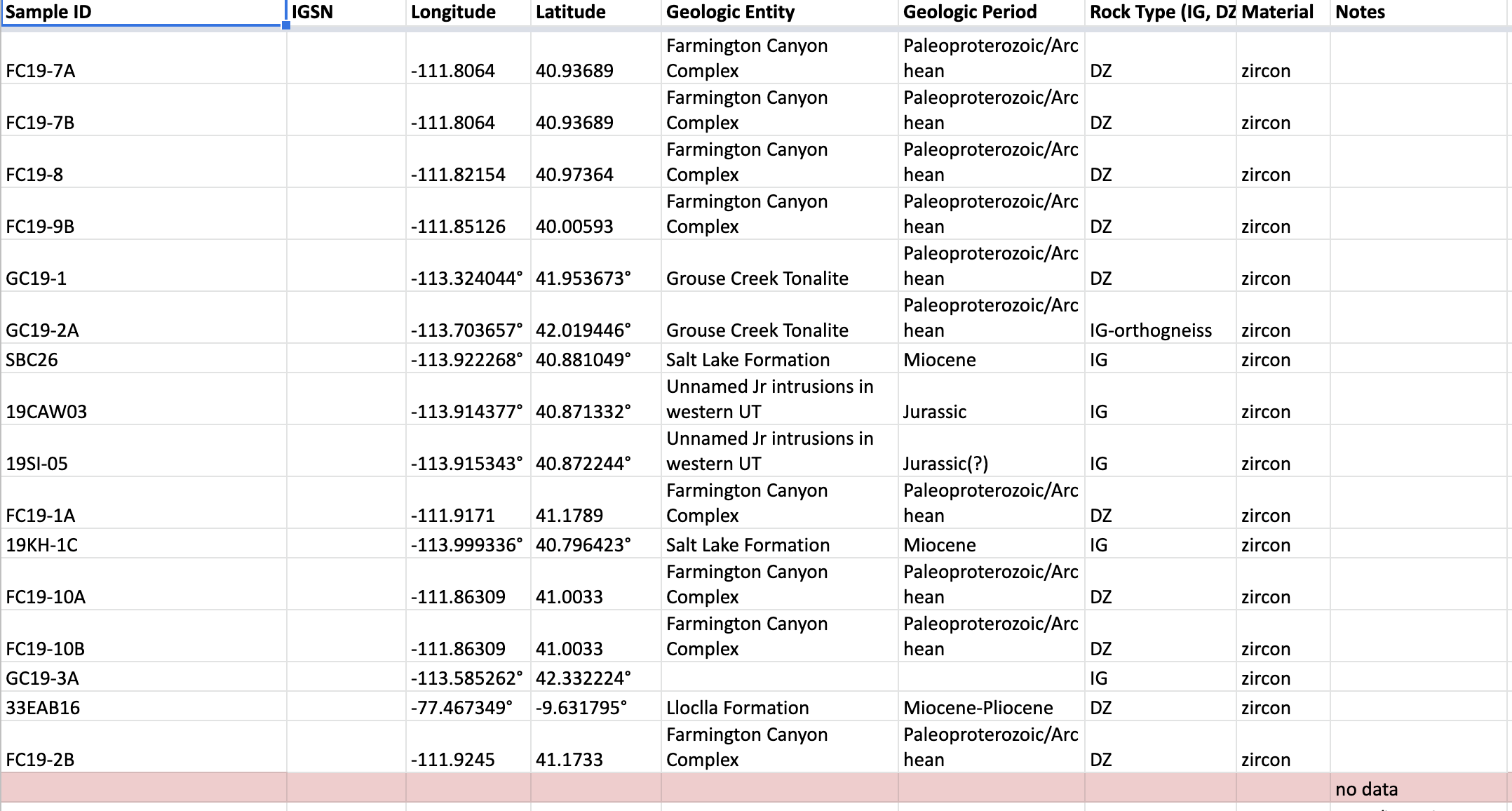

Above you can see a snapshot of the excel file that contains the collection of metadata we will be importing. Even though the data was entered into a relatively standard format there is still human added variability including differences in reporting of longitude and latitude, empty rows, rows with misscellaneous notes, etc. The first thing we need to is clean the data such that we only have the wanted information to import at the end.

To begin get your data into a pandas dataframe! Pandas provides

many helpful functions for creating dataframes from files. read_excel

and read_csv are probably the most commonly needed.

Immediate feedback is helpful for cleaning data so I recommend python environments such as Google Colab or Jupyter Notebooks.

These allow you to execute code blocks at a time and view output immediately, allowing you to quickly iterate on your script.

In these beginning steps for importers, your code can be wherever you want to work on it. But to integrate it with Sparrow and run the importer, it will eventually need to live in the project directory for your Sparrow Lab Instance (see start a lab instance).

Describing in detail some basic cleaning processes in python are out of the scope of this tutorial; however, I have previously written a basic tutorial for Python for Datascience goes through several Jupyter Notebooks in detail on some of my first python data cleaning iterations when I was first learning python.

As an example below you'll see a function I made to change cardinal direction letters (i.e N,E,S,W) into a true or false value representing if the coordinate is negative or positive.

def sign_check(self, unformatted_str):

"""

Takes an unformatted coordinate string and checks if one of the cardinal directions is in it.cardinal_direction_to_sign

Removes the letter from the unformatted string and returns it and a bool indicated whether it's negative or not.

Will also check for a minus sign

returns (unformatted_string, boolean)

"""

letters= ['N','S','E','W']

neg = ['S','W']

is_neg = False

if unformatted_str[0] == '-':

is_neg = True

for l in letters:

if l in unformatted_str:

unformatted_str = unformatted_str.replace(l, '')

if l in neg:

is_neg = True

return unformatted_str, is_neg

Schema based Importing:

At this point you have cleaned data that is correct and ready to be put into the correct data structure for importing. For this importer we are importing samples with a structure variable to the following:

{

"name": "AME18-201",

"location": { "coordinates": [180, 90], "type": "Point" },

"material": "zircon",

"sample_geo_entity": [{ "geo_entity": { "name": "apex basalt" } }]

}

The hardest part about this step is getting the correct format. Explore the Sparrow schema with one of the tools we've developed here. Once you know what the structure will be aim to create a python dictionary with that format. In the following example, I iterate through a pandas dataframe and create a python dictionary out of every row in the dataframe and then append the dictionary to a list. At the end of the function, it returns a list of python dictionaries, one for every row.

def create_sample_dict(self, df):

""" Create sample dictionary ready for loading """

""" ref_datum: null,

ref_distance: null,

ref_unit: null, """

json_list = []

for indx, row in df.iterrows():

obj = {}

obj['name'] = row['Sample ID']

if str(row['Material']) == 'nan':

obj['material'] = None

else:

obj['material'] = row['Material']

if str(row['Geologic Entity']) is not None:

geo_entity = {'name': str(row['Geologic Entity'])}

if str(row["Geologic Period"]) is not None:

geo_entity['description'] = str(row['Geologic Period'])

obj['sample_geo_entity'] = [{'geo_entity':geo_entity}]

obj['location'] = None

if row['Longitude'] is not None:

obj['location'] = {"coordinates": [row['Longitude'], row['Latitude']], "type":"Point"}

json_list.append(obj)

return json_list

Now for the actual importing. For this step there is a simple function provided by Sparrow that takes the structured data list we created in

the last step and imports it into the Sparrow database. That function is db.load_data. This function takes two arguments: 1) a string of the

model name we are importing, 2) the data list. For example for this importer the function call would be:

db.load_data('sample', structured_data)

Integrating with Sparrow

At this point, you have a nicely cleaned dataset a pipeline to create the schema based structure. The easiest way to get your importer integrated with Sparrow is to turn it into a Sparrow Task. This will allow you to run the importer from the frontend of Sparrow and see the output in real time. Creating a Sparrow task is easy and can be done relatively quickly with just a few lines of code (see below).

from sparrow.task_manager import task

import sparrow

@task(name="import-laserchron-metadata")

def import_laserchron_metdata_(filename:str = "alc_metadata.csv"):

"""

importer as a task

"""

MetadataImporter = sparrow.get_plugin("laserchron-metadata")

MetadataImporter.iterfiles(filename)

As you can see in the first line we import task from sparrow.task_manager and place it above a

python function, import_laserchron_metadata_, as a decorator. The technicals of python decorators

is an advanced topic, but for now just remember that you use the @ in front of it. Full code.

The function import_laserchron_metadata_ takes in 1 argument which is the name of the file being

imported, and it has a defualt argument if none is passed, "alc_metadata.csv." The function utilizes

the built-in Sparrow function, sparrow.get_plugin() to find the importer I've written as a Sparrow Plugin.

Then I call only one method (function), MetadataImporter.iterfiles(). The defintion for this function

is shown below and can be found here.

def iterfiles(self, filename):

"""

Read in csv and perform some data cleaning

"""

db = app_context().database

here = Path(__file__).parent

fn = here / filename

click.secho(f"Reading data from {filename}", fg="blue")

df = pd.read_csv(fn)

df = df[df['Sample ID'].notna()]

df['Longitude'] = df['Longitude'].apply(self.clean_long_lat_to_float)

df['Latitude'] = df['Latitude'].apply(self.clean_long_lat_to_float)

df = self.drop_unparseable_coord(df)

json_list = self.create_sample_dict(df)

json_list, number_existing = self.check_if_exists(json_list)

total_samples= len(json_list)

successfully_imported = 0

for ele in json_list:

try:

db.load_data('sample', ele)

click.secho(f"Inserting sample {ele['name']}", fg="green")

successfully_imported += 1

except Exception as e:

failed_import(ele['name'], e)

click.secho("Finished Importing Metadata", fg="bright_green")

click.secho(f"{number_existing} samples already existed and checked for new metadata.", fg="bright_green")

click.secho(f"{successfully_imported}/{total_samples} successfully imported!", fg="bright_green")

In this iterfiles() function I get the file from local storage, clean the data with the other functions defined

in this class (i.e self.clean_long_lat_to_float), and then at the end I try to import the data using

db.load_data() and I catch any errors using a python try and except.